Neuroscience Applied to the Therapeutic Milieu

by Jerry Yager, Psy.D, & Matthew Bennett, MA, MBA

Introduction

A vast majority of the young people treated in the Child Protection, Mental Health and Juvenile Justice Systems have experienced exposure to chaotic, abusive, neglectful, or violent environments in their lives. Although the exact prevalence of abuse and neglect varies, there is agreement that a significant number of youth in these populations have experienced exposure to overwhelming adverse life experiences. The impact of their exposure to traumatic stress has resulted in long-term biological, psychological, and social changes (Perry, 2006). Isolated traumatic events tend to produce a conditioned, biological response to cues associated with the memory of that event. In contrast, for youth who grow up experiencing chronic maltreatment and then are the victims of an isolated traumatic experience, such as a sexual or physical assault, the adverse experience has a more pervasive effect on their development.

Developmental trauma and chronic exposure to maltreatment during early childhood interferes with the organization and functioning of the brain's regulatory systems, which results in an increased need for mental health, correctional, medical, and other social services. Research has confirmed that exposure to early childhood maltreatment sets a negative developmental pathway that will result in not only problems for the child but impacts all relationships that the child encounters throughout his or her life (van der Kolk, 2006; Perry, 1998, 2008; Schore, 2003).

The Adverse Childhood Experience Study provided a link between childhood exposure to violence and other traumatic events and later developing psychiatric and physical disorders and substance abuse. An adverse experience was defined in this study as any of the following conditions in the household prior to age 18: recurrent physical or emotional abuse, contact sexual abuse, an alcoholic or drug abuser in the household, an incarcerated household member, someone who was mentally ill, chronically depressed, institutionalized or suicidal, loss of a parent due to death or divorce and emotional or physical neglect. The study found a significant relationship between adverse childhood experiences and depression, suicide attempts, substance abuse, sexual promiscuity and other involvement in high-risk activities. In addition, the study found that the higher number of adverse experiences reported, the higher the risk for developing, not only psychiatric symptoms but medical problems as well (heart disease, cancer, diabetes and liver diseases) (Felitti et al., 1998). The advances in neuroscience over the past two decades have resulted in new insights on how exposure to early life traumatic experiences can influence development and result in changes in perceptions, feelings, cognitions and behavior. An individual's behavior is a reflection of the world in which they have lived. High-risk, abusive behaviors toward the self, others, or property can be understood as a way the youth adapted to early life relational experiences, which became wired into their neurobiology (Perry, 1998).

Scientific Progress

The goal of neuroscience is to understand how the structures and organization of the brain generate the processes of the mind. Our biological processes result in the expression of the mental processes of sensing, processing, encoding, retrieving, and acting. The underlying conceptual assumption is that all behavior is the result of a brain function (Kendel, Schwartz, & Jessel, 2000). Everything humans do from simple automatic reflexive actions to complex cognitive actions of learning, thinking, and creating is mediated by the brain.

Connected to this model is the acknowledgement that psychiatric and behavioral disorders are dysfunctions of the brain. Over the past three decades, the ability to integrate research from physics, molecular biology, cognitive and social psychology, and neurobiology has allowed us to expand the understanding of the relationship between brain structures and brain functions. The advancement of technology and the ability to witness changes in the brain when systems are activated has created a shift in research from a focus on behavioral manifestations to the underlying neurological processes involved with perceptions, emotions, and cognitions. Neuroscience has become influential in mental health, education, child welfare, juvenile justice, and substance abuse practices. Like all scientific finding, knowledge precedes application.

Awareness of the impact of abuse, neglect, and exposure to violence on the vulnerable developing child's brain and its long-term consequences can lead to more effective clinical interventions within a therapeutic milieu.

For many years a major focus of therapeutic milieus had been on containing the aggressive, impulsive behavior of its youth. The youth are not placed in these therapeutic environments because they have been abused, but because their abuse has resulted in an inability to regulate their emotions and behavior, which resulted in engagement of actions that placed themselves and others at risk. In order to maintain safety, clinically experienced staff are placed in charge

of youth who, if not controlled, would hurt themselves or others. The primary role of direct care staff had the tendency to become the enforcers of rules and the deliverers of consequences for rule violations at the expense of attentive, attuned, and nurturing care. Compliance come to be equated with therapeutic progress and privileges would be earned based upon "good behavior' that complied with adults’ expectations.

In milieus with high levels of stress and anxiety, staff struggles to find their own sense of safety by under or over controlling the youth's symptomatic behaviors. With a focus on behavior management, discipline becomes the primary therapeutic intervention in the milieu. The problem with this framework for childhood victims of abuse is that compliance with adults in positions of authority may have been negatively associated with humiliation, betrayal, terror and an overall

loss of safety in the world. These dynamics get played out not only between staff and youth, but also between staff and staff. Within the therapeutic milieu, some staff perceive others as being punitive and struggle to support their onsequences. Other staff are perceived as over involved and rescuing the youth from being held accountable for their own actions. Tension emerges because there is not a shared, coherent, integrated, comprehensive treatment model that all staff adhere to when organizing observations and guiding interventions within the milieu (Bloom, 2006).

Through advances in neuroscience and the growing awareness of how exposure to abuse, neglect and domestic and community violence impact the youth's developing brain, the understanding of what motivates the youth's actions have changed. The brain mediates behavior in the milieu, school, therapy, family and in the community. Understanding this dynamic allows staff to generate a shared conceptual model for organizing infomation and to guide interventions. Seeing youth as developmentally immature and hurt as opposed to "sick" and "bad" allows for a higher level of empathy and a more humane approach to milieu management. For many adolescents, non-compliance is not an issue of lack of motivation but the result of an inability to cope with environmental expectations and the activation of habitual defensive strategies. Therefore, helping youth cope with overwhelming internal distress and accessing coping resources is not something to be earned for these traumatized youth but something deserved because they are valued individuals. The next part of this chapter will review some neuro-developmental principles and how they shape the understanding of youth and guide the design and interventions within a therapeutic milieu. The last part of the chapter will be focused on creating a safe, supportive relational environment for staff. Such an environment enhances staff's ability to consistently provide the external regulatory function for the developmentally immature youth in their care. The staffs' ability to regulate their own affect and manage change will impact the health of the milieu. A sense of safety is as important to staff as it is to the youth.

Principle #1 - Nature collaborates with Nurture

(Experience-Dependent Development)

For many years the debate about what influence genetics exert on directing development versus the environment was slanted toward genetic determinism. In hopes of understanding the genetic basis of the physiology and behavior, researchers attempted to map out all of human genes. However, the results of these efforts raised many more questions that needed to be answered. If the genes make up the blueprint for development then how do these genes become activated and express themselves in the body?

Biological research has uncovered a mechanism for understanding how genetic expression is modified by the milieu in which they function. The mechanism for gene expression is called "epigenetics." Epigenetic research has discovered that the environment, both the physical and social, can create changes in the molecular structures that mediate gene expression (Masterpasqua, 2009).

Neurobiological research has challenged the concept that the brain became static after the age of seven. It turns out that the brain is constantly changing its structure. Neurons are designed to change in response to internal and external stimulation. This process of neuron changing in response to environmental stimulation is call neuroplasticity. Those neurons that get activated often grow and form stronger, more efficient connections, while those that go unused die and get reabsorbed. As the brain develops and patterned repetitive stimulation activates a particular function, neurons get modified and become established into complex neuronal networks that allow for more efficient integration and sophisticated responses.

When a child is raised within a safe, stable, nurturing environment lower brainstem regulatory functions get organized by the consistent, attuned regulatory interactions with their caregiver. When lower brain regions are well organized, higher brain regions are able to optimally develop. However, when children are raised in stressful, unstable, unsafe environments the lower brainstem's alarm systems are chronically activated. Through a use-dependent developmental modification process these systems become pathologically dysregulated. These youth's stress response systems have a tendency to either over react or under react to environmental stimuli; which interfere with healthy limbic and cortical organization and functioning.

The first clinical implication of this principle is to develop an understanding of the youth's symptomatic behavior within the context of their whole life situation. The youth's current functioning is an outcome of the interactions of their genetic potential and their environmental experiences. A developmental history, looking at the genetic predispositions for physical and mental health issues, as well as, the relational, transitional, environmental resources and stresses the youth experienced should be available to all adults involved in the youth's care. This knowledge should help not only the caretakers but the youth themselves understand that their behavior was an attempt at adapting to their environment, not an indication that they are "damaged goods."

A second important implication is that interventions within the therapeutic milieu should be directed at stimulating particular brain regions. Specific types of stimulation (sensory, physical, relational, and cognitive) should be used with enough repetition so that new neural pathways can be structured and systems will get more organized and efficient. In order to quiet the lower brain regions, which mediate the stress response system, the environment must be safe, physically, social-emotionally and morally (Perry, 2006).

Safety can be broken down into three categories. The first is physical safety, where the youth knows that no matter what kind of violence happens in the milieu others will be there to protect them from physical pain. The second is social-emotional safety, which gives one security that others will respect their thoughts, feelings, and psychological well-being. Finally, moral safety is that the moral and ethical principles that define the caretaker-youth relationship will not be violated (Bloom, 2006). Once a youth feels safe, reparative interventions can be implemented effectively.

Staff must be made aware that if they focus the majority of their efforts at managing problematic behaviors, instead of creating opportunities for the use of new behaviors, old neural networks will be strengthened, while new ones will not grow. When neural connections are activated the probability that they will be reactivated in the future increases. The activation of these connections and networks creates temporary mental states. If staff intervenes after the youth engages in a problematic behavior the probability that the neural pathway mediating that negative behavioral response will occur in the future has increased. "When the temporary mental state gets activated with enough frequency it moves from a state to a trait and becomes more resistant to change. The goal of treatment is to create opportunities for new neural connections to emerge, activating more positive mental states, resulting in alternative behavioral responses. This occurs when the staff supports the amplification of positive affective experiences and provides the support to soothe negative affective experiences.

Developmentally, regulation is an interactive process, with caregivers providing the cortical inhibitory functions, before it becomes an internalized, self-regulatory capability. Validating youth's emotional and physical pain and working with them on developing and using new adaptive coping strategies becomes an important role of the care provider. The first place the youth must learn to feel safe is within their body. In the therapeutic milieu the staff role shifts from being responsible for the youth's behavior to assisting them in learning to monitor their own arousal levels and using new adaptive coping strategies that allow the youth to function within their window of tolerance (Siegel, 2010). The programmatic structures and routines are designed to create a consistency and predictability environment with a moderate level of stress, which allows the youth to successfully practice their newly developed coping skills. The brain changes based upon patterned, repetitive stimulation. As the youth frequently and successfully uses new coping skills, what was initially a cortical cognitive process becomes wired into subcortical, automatic procedural memory. As long as stress is maintained within a tolerable level, youth are capable of using these newly acquired skills.

Treatment is about expanding the youth's window of stress tolerance by assisting in the development of strategies for soothing painful affective states and amplifying the opportunities for tolerating positive affective experiences. When these frequent regulatory experiences occur within the relational therapeutic milieu the youth begins to associate positive affect with closeness to another human being. It is within the relational web of the milieu that healing the wounds of abuse takes place.

Principle #2 - Brain is an organ of adaptation

Evolution selects those qualities that allow a species to survive and then encodes them into the cell's DNA of future member of that species. Humans, being very weak and slow, were extremely vulnerable to the harsh environmental conditions early in the evolutionary process. The solution to this evolutionary dilemma was to become smarter and organize into social groups (tribes) for protection. These individual group members who were smart enough, could remember what not to eat, where not to roam, where to find food, and ultimately survived. The men and women that were able to survive the harsh environmental conditions, bring home food, and learn how to successfully negotiate the relational environment, ended up reproducing and passing on their DNA onto future generations.

Adaptation is also very important because human infants are extraordinarily vulnerable and dependent at birth. The infant is not equipped to physiologically manage the transition from the dark, quiet and warm environment in utero to the bright, noisy, cold world after birth. To survive, the infant requires the protection of their caretakers. The caretakers not only have to meet the infant's needs for food and shelter but actually have to regulate the vulnerable infant's physiology, emotions and attention. Because survival is at stake, the world to which the infant adapts is the world of their caretakers. Regulation early in life is an interpersonal, interactive process where the adult caretaker's brain acts as an extension of the infant's brain to modulate, regulate, compensate and activate bodily functions to maintain physiological equilibrium (Perry & Pollard, 1998). Protection and care of the dependent developing infant became one of the primary directives of the evolving human brain to ensure survival of our species.

Development can be conceptualized as an ongoing process of adapting to increasingly more complex environmental, internal and external demands. Regulation of the response to these demands is embedded into a relationship with the caretakers. The caretakers modulate the quantity, quality, intensity, frequency and duration of the physiological, emotional and social challenges the child faces in their development. When challenges are presented in a safe, nurturing, predictable, gradual and repetitive fashion and match the child's emerging capacities, development is facilitated. However, when challenges are presented in an unpredictable, chaotic, prolonged, threatening fashion and exceed the child's internal and external resources to cope, development is inhibited.

A therapeutic milieu can be understood to be a deliberately designed environment that provides youth and their caretakers developmentally appropriate challenging experiences. When this is done in a safe, nurturing, predictable, gradual, repetitive fashion it facilitates biological, emotional, cognitive and social growth and healing. The daily life demands are kept within a youth's window of tolerance, increasing stress to the edge of their tolerance without overwhelming their capacity to effectively cope.

In designing a therapeutic milieu structuring becomes essential for creating safety and predictability. Many youth that enter these treatment settings have been raised in chaotic, unsafe and unstable environments. Many of these youth have experienced the pain, humiliation, and betrayal of being used for the gratification of an adult's needs and the discounting of their own needs and body. Often they are unaware that their current problems are the result of having to adapt to coping with their early life abusive experiences. The majority of their resources have been focused on survival strategies that keep their defensive systems on continual alert for potential danger and interfered with the healthy development of inhibitory higher cortical functions. These neurological deficits may manifest in increased impulsive, aggressive actions or the frequent use of dissociation. These youth cannot progress in their development until they feel safe, secure and supported (Gaskill, 2009).

Unless the youth feels safe, their biological resources will be allocated toward protection and the activation of subcortical brain structures associated with those functions. When the external environment is predictable and safe the youth can anticipate events in their environment and begin to use top down, cortical functions to organize, plan, and strategize adaptive behavioral response. This gives the adolescent the ability to choose a response rather than reacting in an automatic, habitual manner. With repetition, the connections between cortical regions and lower regions get strengthened and the efficiency with which cortical regions can inhibit lower more reactive regions improves.

Schedules and routines allow vulnerable youth who grew up in chaotic environments to anticipate changes and prepare themselves for transitions. Through consistency, with developmentally appropriate proximity to caring attuned adults, youth will begin to feel safe and secure and expand their capacity for managing risks. Like early parenting relationships these structures and routines are not designed for punishment but to provide the environmental scaffolding necessary to facilitate healthy development.

The structured, consistent way youth are brought into the milieu sets the context for treatment and allows the youth to anticipate what they can expect from this strange environment that probably looks like nothing they have previously experienced. Even though the placement is designed to increase the youth's sense of safety, novelty is always initially perceived as threatening by the brain. In evolutionary terms it was always better to assume danger and stay alive than it was to assume safety and be eaten!

Ways to introduce new youth into the milieu:

Welcome new youth to the program. When possible assign another youth to mentor the new member for the first few days. Staff's primary role is to connect and support youth in their transition. Focus on learning youth's strengths that might be used in treatment (interests, hobbies, abilities, positive experiences).

Explain that structure provides safety. Predictability and consistent rules and schedules help everyone feel less anxious. Staff needs to explain to the youth that the milieu's structure is designed to focus on learning and healing. Staff should help youth who come from chaotic environments to understand that they may initially find this structure uncomfortable.

Introduce staff and explain their roles. Help new youth understand how staff schedules work and how everyone has a role in supporting their treatment. If possible have pictures of staff that will be directly involved with their daily care so they attach a face to a description.

Review all emergency procedures. All emergency procedures should be reviewed with youth assuring them that someone will be available to direct them in case of a true emergency. Explain that staff go through extensive training to ensure their safety in crisis situations. Reviewing fire drill evacuation procedures) medical emergencies, weather related drill (hurricanes, earthquakes, tornados), what happens when there is a need for physical separation between a group and an out of control adolescent and to whom and how they can report any incident in which they feel their safety has been compromised.

Go over all rules. Staff should take time to introduce and explain the rules to the youth. Rules should be kept to a minimum and easy to remember.

• Be respectful to yourself and others

• Be where you are expected to be

• Be responsible for working on your own treatment

• Be supportive of others working on their treatment

• Be a positive community member

Review daily schedules. Explain any groups, classes or therapies and who will be facilitating them. Cover meal times and how to know what food will be served.

Develop safety plan. Explain that everyone in the program has an individually designed safety plan. These plans should identify potential high-risk situations, strategies to cope with situations (sensory, cognitive, physical, social techniques), and potential supports to assist in times of severe emotional dysregulation. As staff get to know the youth, the plan can be further modified.

In order to maintain safety, limit setting and the establishment of boundaries becomes an important function of responsible adult caregivers. Youth often function at a significantly lower emotional developmental level than their chronological age, size, and physical capacities. This demands that adults provide well timed, socializing interventions. When a youth is engaged in activities that staff deems unsafe or inappropriate, a limit should be set. When youth are engaged in actions that the staff determine are a violation of a milieu rules, it is important that staff understand that while engaging in these unsafe actions or programmatic rule violations the youth were experiencing a positive affect state, which is physiologically generated by rewarding and soothing neurotransmitters. When a limit is set, the youth is rapidly transitioned to a negative affect state generated by the activation of their stress alarm response system.

For the emotionally immature youth this transition occurs too rapidly for them to self-regulate. It is at this time that the developing higher cortical regulatory capacities of the youth are overwhelmed and brainstem mediated automatic defensive, impulsive and aggressive actions emerge. The youth's reaction may range from a cognitive challenging of the rules, to a verbally or physically aggressive response or cognitively shutting down and not responding. These youth depend upon the structure of the milieu and well timed, developmentally appropriate, attuned response from a well regulated staff to help soothe their internal distress and enable them to reestablish equilibrium. Engaging in dialogue that attempts to teach or have the youth assume responsibility will be ineffective until physiological equilibrium is reestablished.

This disruption/repair process allows the youth to learn that when life events make them feel bad they can recover. The knowledge that they can handle something, or that there will be somebody there to help, allows youth to take increasingly more risk. Eventually, the youth learns not only to adapt to the rules of the program but also to move from reliance on interactive regulation to self-regulation.

Therapeutic Limit Setting

• Identify behavior that must be interrupted

• Validate youth's need for behavior

• Label emotion and relational impact of behavior

• Provide alternative options for getting underlying needs met

• Recognize the effort involved in complying with request

• Teach after equilibrium has been reestablished

The clinical implication of the principle of adaption is that youth's current behavior was initially adaptive in the environment they were raised in and that new therapeutic milieu is uncomfortable and unfamiliar. When the youth perceives threat they will engage in behaviors that were successful in helping them survive in the past. The youth is processing current sensory information, comparing it to previous experiences and then basing their behavioral responses on their anticipated outcome. It is only after a high number of positive relational therapeutic interactions within the milieu that youth can begin to imagine a different future than their past. Because of the brain's ability to change in response to environmental stimulation change is possible. However, because survival is at stake even if the staff have ten positive interactions, one negative interaction will become evidence that adults cannot be trusted. It is through the process of working through these relational ruptures that new neural networks can be established.

Principle #3 - Brain development is hierarchical and sequential

The brain can be conceptualized as having four major regions, brainstem, diencephalon, limbic system and cerebral cortex (Perry, 2006). Although the brain functions as an integrated whole, it is comprised of systems that are hierarchically organized. This hierarchical organization represents an evolutionary and developmental history with more primitive, instinctual functions being mediated by the lower brainstem and progressing to higher regions with more complex social-emotional function, mediated by the limbic system, and most sophisticated cognitive functions are mediated by the cortex. Each hierarchical level processes different types of information, which can then become integrated into flexible, adaptive response.

The brain develops in a sequential pattern from the bottom to the top, inside-out, back to front, and right to left. Lower parts of the brain develop and organize earlier. Optimal development of higher regions depends upon the optimal functioning of lower regions. The brainstem, the oldest region of the brain) governs the internal environment, homeostasis of the body and arousal. This part of the brain is functional at birth and responds to sensorimotor stimulation. It makes evolutionary sense that people are born with the capacity to respond to threat and alert the caretaker of distress. Survival as a species depended upon this capability.

The diencephalon, which develops early in life, is primarily responsible for the coordination of movement and the integration of sensory information. It organizes over the first few years to allow for the development of increasingly more complex fine and gross motor abilities. It is at this level that sensory stimulation from multiple modalities (sight, hearing, and touch) is integrated before being processed in high brain regions (Kendel, et al., 2000).

The limbic system, which surrounds the brainstem, mediates social/emotional learning and memory The limbic system structures are designed to scan the environment for potential threats and make hormonal adjustments to the internal environment, activate fixed behavioral responses, motivate people to move toward or away from the stimuli and then document that information for future encounters.

The last to organize is the cortex. It has the capacity to integrate information from below and inhibit, organize, and modulate subcortical responses. It is at this level that humans are capable of engaging the capacity for symbolic representation that allows the expression of language, use of abstract thought, development of alternative problem solving strategies and the ability to weigh out the consequences of actions before engaging in a behavior.

The executive functional capability of the cortex, which makes humans unique in the animal kingdom, allows individuals to reflectively alter automatic reflexive reaction. These higher cortical mediated brain functions emerge slowly during development. Infants and toddlers have little control over their emotional and behavioral reactions to distress. They depend upon adults to recognize their distress and take action to respond to their needs. Developments of these higher cortical modulating functions emerge as a result of thousands of relational responsive regulatory interactions by attuned, empathetic caring adult that get wired into the organization of the child's brain.

Youth who have histories of exposure to traumatic, adverse experiences, struggle with developmental deficits to their ability to internally regulate emotions. These youth become easily overwhelmed and lack the capacity to integrate their emotions into an adaptive, flexible behavioral response. They are disconnected from their bodies, physiological states and emotional sensations that could inform them of what they are feeling and guide them in formulating an organized, adaptive behavior response. Failure to consciously identify what is happening inside their bodies interferes with their ability to recognize their needs and take care of themselves. These deficits also interfere with their ability to recognize the states and needs of others and increases these youth’s risk to be victimized or to perpetrate abuse (van der Kolk, 2006).

In the therapeutic milieu some youths' arousal systems become over sensitized and respond to neutral stimuli that have become associated with traumatic experiences, as threatening. Feeling unsafe, these youth engage in defensive reactions that might be impulsive and aggressive, making the milieu unsafe for others. Other youth. whose adaptive strategy is to become withdrawn and dissociate may miss important danger signals in their environment and place themselves in high-risk situations. Most of the youth being treated in the milieus will have a tendency to rely on both of these adaptive strategies at different times and in different relational contexts. Although the behaviors look very different, the underlying drive is protection and survival.

Risk management is another important function in the therapeutic milieu. An awareness of youth's past histories, vulnerabilities and risks for engagement in abusive, self-destructive behaviors is an important function of supervising staff. Denial of a youth's risk factors places them, other youth, staff and the entire community at risk. Their inability to protect themselves or manage their risk of harming others must be understood in terms of their developmental and relational deficits and not a judgment of their worth. Policies and procedures must be implemented to know the whereabouts of youth and to effectively monitor their interactions, while affording them developmentally appropriate levels of privacy. When critical incidents do occur in the milieu, they should be debriefed and used as learning and growth opportunities. Safety should be the number one priority of every staff person in the milieu.

The clinical implication of the sequential development of the brain and the awareness that functioning of higher brain regions depend upon the optimal functioning of lower brain regions suggests that interventions should first focus on symptoms that are mediated by the lower brain region. Dr. Perry (2006) states:

In order to influence a higher function such as speech and language or socioemotional communication, lower innervating networks must be intact and well regulated. An overanxious, impulsive, dysregulated child will have a difficult time benefiting from services targeting social skills, self-esteem and reading (p. 243).

As long as lower brain regions are functioning ineffectively, high brain mediated functions will not show improvement. Interventions need to be directed initially toward regulation of lower brain, arousal systems. Neurological principles and research (van der Kolk, 2006; Perry, 2009) suggest that experiential therapies and activities that focus on stimulation and awareness to physiological sensations provide input into the brainstem and diencephalon and promote increased neurological integration. Recognizing and learning language to communicate sensations within the body is an important skill to initially work on with youth in the milieu. The attuned staff might observe postural or facial changes that reflect a change in a youth's physiological states before the he or she is even aware of them. Helping youth learn to observe what is happening within their bodies, without casting judgment, and communicating their observations is an important developmental skill. Recognizing sensations within the body allows the youth to recognize when they are feeling unsafe, over stimulated or under stimulated and then use this information to develop an adaptive behavior response.

Yoga, music, martial arts, physical exercise, dance, therapeutic massage and treatments that focus on the body, (e.g., drama, mindfulness, occupational therapies) are recommended for working with traumatized individuals. Once the lower brain has been regulated, more traditional talking approaches become more effective. In order to create a developmentally responsive therapeutic environment a wide range of experiences must be embedded into the program design, that focus on cognitive information (academics and psycho-education), emotional stimulation (amplification of positive emotional experience and soothing of negative ones) and sensory-motor activities.

These activities will not be effective unless they are built into the interactional structures of the relational environments of the milieu. These alternative forms of stimulation should be delivered frequently, for short durations instead of the traditional 50 minute hour. The power of the milieu is that the number of interactions necessary to create neural changes does not occur not within the therapy session but in the interactions with childcare and teaching staff. A therapeutic milieu has to provide the containment that keeps the youth, staff and community safe but containment, although necessary, is not sufficient to facilitate growth.

Daily therapeutic activities (Perry, 2006; Gaskil, 2009)

• Activities should be matched to the youth's developmental age in a given domain (physical, social, emotional, cognitive).

• Activities should take place within a healthy relational environment, in which youth are developmentally appropriately supported, challenged and positive effort are recognized, not just outcomes.

• Activities should be provided with enough repetitions and durations to achieve the desired therapeutic change.

• Activities must be rewarding. A caretaker's role is not only to provide soothing when youth is in distress but also to find ways to amplify positive emotional experiences, which widens an individual's capacity to tolerate affective arousal.

The clinical implication of the principle of hierarchical and sequential development is that treatment planning has to replicate the sequential developmental process. Interventions that target cortical mediated brain functions have to follow those that focus on lower regulatory functions. This principle is also useful when dealing with youth in a fight/flight or dissociative state. The staff interventions have to first reestablish safety, both within the youth's body and in the environment. This can be accomplished by helping the youth focus on their breathing, physical movement, or other previously identified coping strategies. Next, staff want to focus on repairing the relational rupture before moving into cognitive interventions, designed to verbally process the experience and take accountability for ones actions.

Principle # 4 - Mirror Neurons and Relational Templates

As a species, human survival has depended upon the other people in the environment. The unfortunate reality is that, at times, people have been the greatest threat to survival. Humans had to develop specialized neurons to read the intentions of others to ensure survival. The human brain is incredibly sophisticated at picking up sequential patterns in the environment in order to anticipate and predict what is ahead. The brain hates surprises.1 Humans have a system of neurons that map out not only the behavioral intentions of others but also their underlying emotional states. These groups of mirror neurons allow us to resonate with the internal state of others and sense what sequence of action is coming along with the emotional energy that motivates those actions (Siegel, 2010).

Embedded into infant-mother interactions are non-verbal communications, processed by the early developing right-brain structures that synchronize the biology of the mother and child. By sensing her own internal state, she is able to recognize and understand the internal state of her child. She then responds, and with her knowledge of her child's experience her response is accurately attuned to meet the child's needs. As a result, these accurately attuned interactions between the mother and her child activate a social reward system in both of their brains.

Two important developmental processes are being established during these interactions. First, the child is learning to tolerate and value their own internal states, and secondly, they are beginning to find pleasure in socially interacting with others. For many traumatized youth, their early relational interactions were not accurately reflected. Their caretakers were either unaware of their non-verbal communication (maternal depression, neglect) or the communication placed too great a demand upon the caretakers own regulatory repertoire and they responded to their own needs and not the needs of the child. These interactions left the child feeling invalidated and misunderstood. These children could not find the pleasure in social interactions and learned to adapt by dissociating to their misattuned world.

Memories are not stored in a single system, but are composed of different systems that work together, in an integrated manner when these networks are functioning well. The memory system most of us recognize easily is the verbal or explicit memory system. These are memories that we are conscious of and can be declared to others and ourselves. We experience these memories as having happened in the past, with a beginning, middle and end. If you were asked to remember learning to ride a bicycle and who was in that experience, certain pictures would emerge that you could share with another person. This is an explicit memory.

A second, earlier developing, wordless memory system records experiences in sensations, images, feelings, automatic behavioral reactions, and perceptual biases. All memories in the first 12-18 months of life are recorded in the implicitly system.

These memories function outside our conscious awareness but influence our actions on a daily basis without pictures and words to connect them to earlier experiences. These memories form the foundation of our relational mental models, influencing our expectations of ourselves, others and the world (Siegel, 1999).

Many youths' dissociated, painful experiences are communicated to staff through non-verbal, right brain and unconscious processes. Their earlier relational traumatic experiences are stored in the implicit memory system that gets reactivated within the caregiving therapeutic relationship. Youth do not experience their body sensations, feelings, images, and behavioral impulses as memories from the past but as experiences in the present. An example of this process occurred when a 16-year-old female, residing in a residential center, had been removed from her biological family due to a history of severe neglect, while her siblings remained in the home. In therapy she would express her feeling of anger at her mother for not fighting to keep her but only her siblings. Although she was able to express her rage she demonstrated minimal insight into how this painful experience influences her current relational interactions. One day, while this client was in class with eight other students, the teacher was helping one of her peers with a math problem. This young lady turned over her desk and started yelling at the teacher that she likes the other child better and wants to get her thrown out of the school. For safety reasons the girl had to be removed from the classroom and she told her therapist that she is sure this teacher doesn't like her and is out to get her in trouble. Re-experiencing her traumatic past she selected the female teacher to play an important role in her life's drama. Initially, the therapist felt herself getting angry with the teacher and protective of her client. The attuned therapist used her internal experience to focus on the girl's feelings of being unwanted and unsafe, instead of focusing on her disruptive behavior or the teacher's behavior. After the girl felt understood she was in a mental state to look at the impact her behavior had on the safety of the classroom and how she could repair these ruptured relationships. She was also able to begin to explore how her past experience of rejection from her biological family biased her perceptual interpretation of the teacher's behavior and her own sense of self worth.

The ability of the healthy staff to reflect upon their own internal experiences and derive an understanding of what a youth is experiencing is the basis of empathy: Caregivers can actually feel the youth's internal experiences by reflecting upon their own internal experiences. With empathic connections there is an assumption of difference between what the staff think the youth is experiencing and their actual experiences. Empathy is just an approximation.

Communicating these empathetic perceptions allows the youth to feel understood, valued, and soothed. Maintaining a psychological boundary enables staff to work with the youth's problems without being overwhelmed by them. Through frequent emotionally attuned and connected interactions with the staff, the youth begins to modify existing relational templates and is able to differentiate between what happened in the past and what could possible happen in the future. Youth can begin to integrate these experiences into explicit memories and create a coherent narrative of their lives (Badenoch, 2008). This is the foundation of hope, which motivates youth to change.

However, if staff just focuses on managing behavior, they miss important teaching moments and regulatory opportunities to validate the underlying emotional needs of the youth. This replicates the neglectful world in which the youth grew up in and may trigger associated painful past memories. A particular staff with a certain gender or other characteristic begins to play the role of the victim, perpetrator, or rescuer in the eyes of the youth. The potential for this dynamic to get played out in the milieu is intensified by the caretaking roles played by staff and the youths attachment history Without structure and support staff may become reactive to the stress generated by the youth's dysregulated affect and may respond by becoming either overly authoritative or overly gratifying of the youth's needs. These relational interactions between the staff and the youth are driven by past relational templates mediated from lower brainstem and limbic regions, without the benefit of cortical-modulated and consciously developed choices. These templates are activated outside the awareness of individuals involved in the interactions. Almost any interaction with youth who have traumatic histories can be experienced as an empathetic failure and results in a relational rupture. These ruptures trigger painful memories, which the youth might not be consciously aware of, and are accompanied by distressful internal states. Unaware that these painful internal states are generated by the activation of unconscious, irritating, implicit memories, youth target the staff as the cause of their internal discomfort. However, even when the staff are well attuned to the youth's underlying needs, this newly experienced relational connection with another may trigger intense emotions and make the youth feel vulnerable and anxious. When anxious, the youth attempts to protect themselves by engaging in automatic, patterned, defensive reactions.

The suddenness, intensity and often randomness of the youth's reactions to these relational interactions challenges the staff's own sense of safety and triggers the staff's stress response system as they attempt to cope with feelings of loss of safety, competence, powerlessness and helplessness. If the staff is unable to take the time to reflect upon their own internal experiences and develop consciously driven responses, they will act to protect themselves. Based upon their own relational histories, they may move to distance themselves from the affect through intellectualization, power and control decision making, blaming or seek to move closer to the youth by over identifying and gratifying, attempting to fix the youth's feelings. These automatic, unconscious defensive reactions interfere with the staff's ability to empower the youth regain a sense of safety, security and internal control.

Everyone that interacts with the youth or staff involved can begin to resonate with the affectively charged non-verbal, implicit communication. Other youth begin to react to the sensed loss of safety and engage in their defensive, symptomatic behaviors, targeting staff as the cause of their distress. Staff, feeling unsafe and vulnerable, begin to impose increased control and restrictions as a way of managing the groups stress reactions. Through a process of over generalizations of past abusive associations the youth begin to experience the current milieu as paralleling their early childhood experiences. Unaware that their internal distress is stemming from the activation of painful earlier memories the youth, using their verbal left-brain functions create a current explanation for why they are feeling so distressed. Often times the explanation focuses on the staff, other youth or the world at large.

This is when the therapeutic milieu is most challenging but also most powerful in helping youth differentiate between what occurred in the past and what is happening in the present. As staff validate for the youth their internal feelings of distress, that this experience does feel like the past but also communicates that it is not the same as the past, and the youth begins to have relational experiences that are incongruent with their internalized relational mental models. When staff recognize the dysfunctional cycle occurring in the milieu, take accountability for their own emotional reactions, validate the youth's feelings and reestablish a sense of safety, the building blocks for new relational templates are created.

The clinical implication of this principle is that non-verbal, affectively charged communication is occurring constantly with the milieu. Each of the members of the milieu is resonating with the affective states of other members. Emotions are contagious and easily bias our perceptions. Youth within these milieus are extremely sensitive to the affective states of other youth. They rely on staff's ability to feel what they are feeling, digest these reactions and then give them back in manageable doses. The structure of the program bas to be designed to assist the staff in carrying out this important caregiving function. The structure of the program must be flexible to accommodate the changing needs and states of the youth.

Milieu Structural Flexibility

The milieu is designed to be a physically and psychologically safe environment that allows youth to relax their defensive scanning for potential threats and have resources allocated to growing and healing. When the safety of the milieu is disrupted by a significant number of critical incidents (abuse to self, others, or property; runaways) an adjustment in daily structure should take place to increase the level of supervision and support. Slowdowns or shut downs are designed to reestablish safety.

The change in structure is as much for staff as it is for the youth. Initially, the youth will continue to focus on the staff as the cause of their distress. However, when the staff are given the time, support, and supervision to reflect on their own experiences and how it has impacted their perceptions, emotions and behavior they are in a better position to provide therapeutic care to the youth. Staff are able to communicate expectations in a firm, consistent manner while providing validation of the youth’s experiences. When safety is reestablished, youth can begin to recognize and own their reactions and work on repairing relational disruptions. It is through the disruption and repair process that internal relational templates get modified.

The clinical implication of the principle mirror neuron and relational templates is that in order for a therapeutic milieu to allow healing and growth, it must be staffed with healthy workers who can manage their own reactivity, in order to regulate the psychophysiology of the youth under their care. When stress gets too high in the milieu staff must possess the ability to benefit from supervisory support and guidance. This process is dependent not only on the health of an individual staff person but upon the relational health of the team and organization. In designing the therapeutic environment, the organization must prioritize the support and training of their staff who are the primary deliverers of therapeutic care.

As a species we are all designed to act in a way to ensure our survival. When staff assumes a position in a therapeutic milieu, they place themselves in relationships that potentially threaten their well-being. The staff are confronted with stories of great atrocities to others that threaten to challenge their view of the world. They are witness and at times victims of verbal and physical aggressive acts that chronically activates their stress response system. They are being evaluated and investigated by people in the organization and by regulatory agencies that threaten their professional well-being. The staff's experience of feeling powerless, helpless and victimized parallels the experience of the youth in their care.

Strong supervision is critical in helping the staff regulate their emotional responses to the trauma and stress in the milieu environment. Because staff's brains function in a similar manner to the youth they serve, the staff also need strong support and feedback to be successful. All staff will struggle from time to time. They need supervision, support, and resources to help them regulate their affective state and access establish cortical functions, thus helping them make growth facilitative therapeutic choices in their interaction with youth. A therapeutic milieu depends upon healthy, well cared for staff.

The Need for Strong and Reflective Supervision

Studies have demonstrated that work in therapeutic milieus is the second most emotionally demanding job, after only police patrol officers (Bloom & Farragher, 2011). Exposure to youths' stress and trauma put staff at risk for re-experiencing their own trauma and high levels strain due to the nature of die work. Vicarious or secondary trauma is a result of indirect exposure to a traumatic event through a firsthand account or narrative by the youth and the staff’s subsequent cognitive or emotional response. Research shows that up to 50% of staff are at serious risk of suffering from vicarious trauma (Geisinger Health System, 2008). Compassion fatigue is another type of trauma where the staff experiences a gradual lessening of compassion over time when exposed to a series of firsthand accounts or narratives by the youth. While vicarious trauma usually happens at a specific point of time, compassion fatigue is the accumulative effects of hearing youths' traumatic experiences over time (Harris & Fallot, 2001).

In addition to vicarious trauma and compassion fatigue, the staff can also experience active and passive trauma. Active trauma is a boundary violation resulting in a clearly toxic interaction resulting in cognitive, emotional and/or physical injury. It is not uncommon in many therapeutic milieus to be characterized by outburst of verbal or physical violence where the staff experiences emotional and/or physical pain and suffering. If the staff is not supported through caring and resources then another type of trauma may also result. Passive trauma is a form of neglect where the individual does not get the support they need to recover from the active trauma (Lewis, 2006).

The result of the above trauma is devastating on both the individual and the milieu itself. Staff suffering from trauma have been shown to have compromised physical health, disruption of relationships, blurred boundaries, hopelessness, decreased ability to experience pleasure, decreased productivity, constant anxiety, negative attitude, feelings of incompetence and self doubt. This impact is also felt on the staff and culture of the milieu resulting in breakdowns in communication, decreased morale, decreased group cohesiveness, decreased productivity, anger and resentment towards management, increased absenteeism, safety issues and increased turnover (Harris & Fallot, 2001).

Unfortunately, trauma is not the only danger impacting staff in the milieu. Strain and burnout are also common factors impacting the culture and healing ability of the milieu. Strain is the resulting internal biological reaction to a stressful event and causes the anxiety, fatigue, and physical pains resulting from the internalization of stress. Strain releases the brain-toxic stress hormone cortisol. Cortisol decreases the energy supply to the brain interfering with proper function of the brain's neurotransmitters. This results in mental confusion, short-term memory loss and the death of brain cells (Fernandez, 2006).

If strain's intensity continues over a period of time, the staff is at risk of becoming burned out. Burnout happens in four stages: exhaustion; shame and doubt; cynicism and callousness; failure, helplessness and crisis. Burnout can emotionally and cognitively prevent the staff from engaging effectively with youth in the milieu (Bloom, 2006). In addition, burnout can also lead to heart disease, back problems, cancer, mental illness and an increase in aggressive and violent behavior (American Institute of Stress, 2010).

Strain and burnout have a dramatic impact on the ability of the system to provide a healthy milieu. Research has shown that a system with high strain and burnout have increased healthcare costs, increased turnover, increased absenteeism, increased litigation, and grievances, decrease in productivity, low job satisfaction and difficulty adjusting to change. While burnout can prevent the staff from providing services the youth need, it can also paralyze an entire system rendering it totally ineffective (American Institute of Stress, 2010).

The reality is that staff experiencing strain and/or trauma will not be able to effectively regulate their own emotional responses in the milieu, giving them a very limited capacity to assist the youth in regulating their responses and establishing safety. Traumatized and burned out staff are more prone to have negative interactions with youth, mirroring the dysfunctional relationships in the youth's life that led to violence, sexual abuse and neglect. These non-therapeutic interactions force the youth back into their survival and emotionally reactive mind limiting any possibility for positive growth and new ways of living.

Staff Resiliency

The above dangers are inherent to any therapeutic milieu and will occur from time to time in even the healthiest settings. "While it is important to make staff and supervisors aware of these dangers, their causes and warning signs1 it is just as important to focus on the skills and strategies that enable individuals and teams to recover and grow from trauma and strain inevitable in the work of helping. These skills and strategies, known as resiliency, are a key component to healthy staff and a milieu that promotes healing and growth.

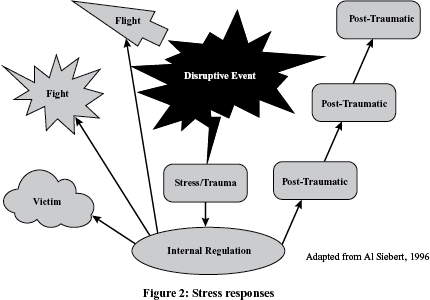

Resiliency is an individual's or group's ability to recover and grow following stressful events. This is accomplished by internally regulating responses to stress, so one can cognitively approach the event and not react emotionally to it. Even the most resilient people feel the grief, anger, loss and confusion associated with trauma, but resilient people do not let this become a permanent state of being. In terms of the brain, resiliency is the ability to process an external event in the prefrontal cortex where the emotional reaction can be managed, allowing the individual to react intellectually thus coping. If resiliency is low, the stressful event is processed in the limbic system leading to a hyper aroused response (flight or fight) or a hypo aroused response (freeze) neither of which can draw on the cognitive resources of the prefrontal cortex.

There are two distinct stages of resiliency. Health resiliency and recovery resiliency both play a critical role in the individuals or group's ability to recovery and growth from a traumatic or stressful event. They also build upon each other to create an internal strength within the person or group allowing them to reframe, find hope and ultimately grow stronger from the experience.

Health resiliency speaks to the health and energy capacity of the individual or group before a disruptive event occurs. The amount of health resiliency an individual or group has depends on their mental, physical, emotional, social and spiritual health. When these factors are strong it allows one to bring more energy and resources to a crisis when it does occur. A strong health resiliency has also been shown to allow people to identify and address issues before they become a crisis, lessoning the amount of strain and trauma that would have otherwise resulted (Valikangas, 2010).

There are two key cognitive processes that impact health resiliency. The first is mindfulness. Rock (2010) describes mindfulness "used by scientists today to define the experience of paying close attention, to the present, in an open and accepting way. It's the idea of living 'in the present,’ of being aware of experience as it occurs in real time, and accepting what you see" (p. 90). This reflection on our internal regulation allows us to cognitively make strategic choices and thus change our thinking or emotional response in the moment.

Mindfulness is a tool for the staff, as well as a skill to teach youth, to avoid emotionally reacting to the stress and trauma associated with the therapeutic milieu. If the staff can remain regulated, then they can assist the youth in regulating their emotions as well. When people act with awareness, the therapeutic milieu can strategically assist the youth in their own thinking and emotional reactions, setting the stage for healing and growth.

Mindfulness in a therapeutic milieu entails being nonreactive to hyper arousal or hypo arousal impulses if the situation does not impose an immediate threat. This is done by observing and attending to what one is thinking, feeling and sensing in the moment and being aware and nonjudgemental of this experience. Being nonjudgemental allows the individual to label the reaction appropriately and not let it drive behavior (Baer, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, Smith, & Toney, 2006).

The second cognitive process impacting health resiliency is the management of expectations. The brain operates at an effective cognitive level when it can predict what will happen next based on past experiences. These predictions or expectations give the brain a sense of control over the environment and allows the brain a context to process incoming stimulus. Stressful events in the milieu challenge the staff's expectations and decrease the rewarding experiences creating a hyper arousal/hypo arousal response (Rock, 2010).

Therapeutic milieus are characterized by unpredictability and crisis. This challenges the staff's expectations that the milieu should be an environment for healing and growth. How can milieus where emotional and physical violence is always a threat, be a place of healing? Having to hold this contradiction often leads to cognitive dissidence, role confusion and a questioning of the nature of the work the staff are doing; are they partners in healing and growth or baby sitters who are only trying to keep the peace. Health resiliency is challenged by this predicament.

Unfortunately, many staff change their expectations of the environment from one of healing to one of crisis control and management. When these expectations change it sets in motion the self-fulfilling prophecy effect where the staff actually contributes to the chaos and crisis in order for the environment to meet their brain's expectations. Without strong supervisor and peer support staff can get lost in this dynamic leading to increased stress and decreased ability to therapeutically engage with clients.

The role of expectations in milieus sets up one of two types of staff mindset. The first is a protective mindset in which the staff's brain is primarily focused on their own safety and minimizing potential risks by withdrawing from the situation when possible. The second is a growth mindset. This is the belief that one's self and others have the capacity for growth and acquisition of new abilities. Traumatized and burned out staff struggle to have a growth mindset and more often than not adopt a protective mindset as a survival technique.

Health resiliency is a combination of overall health with the ability to manage expectations and be mindful of internal processes. Everything from the amount and quality of sleep, to exercise, diet, and the amount of social connections a person has all increase overall health and therefore improves their level of health resiliency. It is impossible for a physically or emotionally unhealthy person to be resilient.

Therapeutic milieus, by design, test staff's health resiliency by placing them in situations that are difficult for their brains to maintain healthy cognitive and emotional functioning. In normal situations the mirror neurons will resonate with the emotional dynamics of the social environment. In the milieu the staff is in charge of many youth, all in the milieu due to their inability to self regulate. With emotions being contagious, the affective state of the youth begins to influence the staff's perceptions and overall mindset. The staff have to be healthy, trained and supported enough to realize this and actively work to maintain healthy boundaries, in spite of a staff to youth ratios that makes this task difficult.

Staff in the milieu rarely are taught about emotional contagion and the impact on their personal health, mindsets and expectations about themselves, others and the world. Exposure to this type of negatively emotionally charged environment, for prolonged periods, can not only change the staff's ability to maintain positive perceptions within the milieu but also in their daily lives. It has been said that "Time heals all wounds but time also has the potential to wound all healers" (source unknown).

The second component of resiliency is recovery resiliency. Recovery resiliency is the ability to recover and grow stronger after experiencing a stress event or crisis. This type of resiliency describes tenacity in the face of a threat in the environment and the capacity to survive the trauma associated with that threat (Siebert, 2005).

The key moment in the brain's reaction to a disruptive event happens when the thalamus chooses whether the environmental stimulus is a threat and needs to be processed primarily in the amygdala or if it is safe enough to process in the slower more accurate, cognitive-based hippocampus and prefrontaI cortex. Mindfulness and managing expectations will set the staff up to cognitively handle the situation through reframing. Reframing is the brains ability to adapt to changes in the environment that do not fit our expectations and past experiences.

When the reality of the milieu does not meet the staffs expectations they will feel stunned, angry, and despair which can result in defensive behaviors, depression and physical and emotional health issues. However, this can be avoided if the brain is able to reframe a situation. Reframing allows the brain to incorporate what is going on with the environment and change or adjust expectations. A staff that is able to reframe and adapt will see a violent event in the milieu as part of the healing process and not a threat to the core of what the milieu is about (Rock, 2010).

Reframing is difficult if not impossible for staff suffering from vicarious trauma or burnout. When staff experience trauma or strain, they rely on early attachment relational templates stored in the lower regions of the brain. For those staff with a secure attachment, maintaining a growth mindset and reframing is natural. However, for staff with insecure relational templates, finding relief from distress is a challenge. This often results in a reactive and protective mindset that does not allow reframing or realize reframing's positive benefits that lead to growth and recovery.

If the brain is able to cognitively define the situation through reframing it can find motivation in hope that the crisis will lead to growth and learning. This moment where a crisis is reframed as an event for learning and strengthening is called post-traumatic recovery. While staff might be still experiencing some emotional fallout from a crisis, their brain has adapted its expectations that the overall outcome will be a positive one.

The ability to reframe relies on having a core of knowledge on the dangers of vicarious trauma and strain. Research has demonstrated that the best way to keep staff healthy in the work of helping is to train them on the dynamics and dangers of vicarious trauma. Putting a staff in a milieu without this knowledge is like putting a driver behind a wheel of a car without first teaching them how to drive; the consequences put the staff and all those in the milieu at danger (Bloom, 2006).

This leads to the last aspect of recovery resiliency: post-traumatic growth. Post-traumatic growth takes place when the hope of pest-traumatic recovery is realized and new strength is gained. Post-traumatic growth increases self-efficacy in staff by raising their confidence in their personal strengths. In addition, post-traumatic growth strengthens the relationships with those they experienced the crisis with whether that is staff or the youth. Post-traumatic growth also increases health and recovery resiliency for future stressful events as the brain now has the expectation that it can handle and grow from future crisis (Rock, 2010).

Health resiliency and recovery resiliency are skills that staff in the therapeutic milieu must master for the healing of the youth and for their own health. Resiliency gives the staff the ability to meet the trauma and strain of the youth with a healthy response. This models healthy behavior and gives the youth confidence that the staff can help them regulate their own emotional responses and not react to them negatively.

Role of Teams in the Therapeutic Milieu

The human brain developed in families, tribes and other groups that were a critical component of survival whether in the savannas of Africa or the frozen world of the ice age. While social connections have always been seen as valuable "some scientists now believe the social needs are ... as essential for survival as food and water ... the brain interacts with social needs using the same networks as it uses for basic survival" (Rock, 2010, p. 158-159). In the stress and trauma of a therapeutic milieu these social connections manifest themselves in the teams that run therapeutic milieus.

Strong social bonds with team members is shown to increase overall well-being, lower stress, stabilize mental health, increase performance, multiply our emotional and intellectual resources, create a greater sense of purpose and - maybe most importantly – increase resiliency. The health or toxicity of the milieu is often a direct reflection of the health or toxicity of the team in charge of its operation. If relationships between team members are strong, it gives a foundation for establishing healing relationship with the youth.

Teams follow many of the same patterns of resiliency as individuals. The resiliency of teams is determined by both the resiliency of each team member and the collective synergy of the team. A healthy synergy incorporates diverse perspectives and creates a space for each member to contribute their strengths for the success of the entire team. Synergy is also a result of a team design that is flexible enough to proactively head off disruptive events, and that is responsive enough to bring resources and capacity to a crisis when it does occur (Hoopes & Kelly, 2004; Valikangas, 2010).

Health resiliency and recovery resiliency also determine the effectiveness of a team within the therapeutic milieu. The health resiliency of teams is determined by the strength of their social bonds and the healthy boundaries established by the team's norms. These social bonds allow team members to help other members self-regulate their responses to stressful events. If the team operates in a cognitive capacity, it can support members’ emotional reactions by assisting in mindfulness and managing expectations of the reactive member. A resilient team also structures their social bonds around shared expectations and goals. A resilient team operates with a collective mindset while incorporating each member's personal strengths (Hoopes & Kelly, 2004; Valikangas, 2010).

The team's mindset also impacts its recovery resiliency. High functioning teams in therapeutic milieus have a collective understanding that giving up is not an option. Difficult youth and situations are seen as challenges to overcome and not inconveniences or disruption to the culture of the milieu. Resilient teams are able to adapt when the environment or the milieu does not meet with established expectations (Hoopes & Kelly, 2004; Valikangas, 2010).

Role of Supervision in the Therapeutic Milieu

The final component of a healthy therapeutic milieu is supervision. Supervision is critical to the operation md health of the therapeutic milieu. While there are many operational aspects of supervision, this section will focus on the affective regulation of staff. Affective regulation is where the supervisor assists the staff and the team to manage their emotional reaction to events in the milieu.

Affective regulation is all about the relationship between the supervisor and the staff. Unfortunately, strong relationship between supervisors and their staff is not the norm. A recent study showed that spending time with their supervisor was the worst part of the staff's day, and people rated time spent with their boss lower than doing chores and cleaning house. The unfortunate effect of these broken relationships is dramatic. In studies with adults in a variety of work settings, those who deemed their supervisor least competent had a 2 4% higher risk of serious heart problems while those who had worked for that supervisor for more than four years raised that risk to 39% (Rath & Harter, 2010).

This speaks to the toxicity that exists in many organizations and how it impacts the staff attempting to manage the milieu. Toxicity is defined as a variable (in this case the supervisory relationship) that causes damage to a system (in this case the milieu). Research shows that an increase in toxicity in relationships has a direct relationship to a decrease in staff morale. This decrease in morale has the impact of decreasing individual performance, which then decreases the quality of care in the milieu. As the quality of care in the milieu decreases toxicity increases and the cycle continues with increased negative results (Lewis, 2006).

Fortunately this cycle can run the opposite way with increased health replacing toxicity where morale and individual and organizational performance rise. The key to moving this cycle in a positive direction is a health relationship between the supervisor and staff. Key components of the supervisory relationships keep staff healthy and lead to desired treatment results.

The core of this relationship must be based on a foundation of supervisory integrity. Here integrity is defined as the supervisor's honesty, humility and ability to care about their staff as people. While honesty and humility are self-explanatory, the caring piece is often not. Since our brains evolved and developed within families or tribes, feeling cared for and connected meant survival. This explains why people work harder when they feel their supervisor cares about them as a person and not just someone performing an organizational task. When we do feel cared about it increases trust, creates shared mental models around goals and expectations, increases collaboration and commitment, and decreases turnover by 22 % to 37% (Wagner & Harter, 2006).

The supervisory relationship must also be built upon a strong sense of trust. If trust is established, our brains release oxytocin. Oxytocin increases feelings of calm and safety and allows one to be mindful of cognitive and emotional responses. If trust is not established and instead toxicity occurs the brain will release dihydrotestosterone, which leads to aggressive behaviors as more variables in the environment will be interpreted as threats (Wagner & Harter, 2006).

One could think of the milieu as a balance between oxytocin and dihydrotestosterone. Traumatized youth can be expected to have a high level of mistrust and dihydrotestosterone from years of adults failing to meet their needs and being hurt physically and emotionally. It is the job of the milieu staff to try to build trust and safety in order to create an environment for healing.

Trust and safety can only happen consistently if the organizational culture has a high level of trust throughout its structure. Simply put, trust is a combination of someone believing their supervisor will do what they say they will do and that the staff can predict the quality of the supervisor's work. Trust is such a powerful component of the staff/supervisor relationship that is has been shown to decrease turnover by half (12.6% versus 25%), increase productivity, increase the ability to learn new material, decrease and staff aggression under stress. Without trust, staff will struggle to effectively engage with clients and to control their own levels of stress and frustration (Bloom & Farragher, 2011; Buckingham & Coffman, 1999).

Another key aspect of creating trust is the effective management of conflict between individuals and within teams. Unresolved conflict "impedes group performance by limiting the ability of individuals or groups to process information and to think well. It also diminishes group loyalty, team commitment, intent to stay at the organization, and job satisfaction because of escalation in levels of stress and anxiety" (Bloom, 2006, p. 101). Conflict is a result of the brains reaction to a perceived threat. This reaction leads to either an active withdrawal from the threat or an active attack against it.

A supervisor must be intuitive enough to identify conflict and strong enough to confront the root causes of the threat. Since most conflict involves emotional reactions of the parties in conflict, the supervisor is well positioned in the syste1n to react cognitively and repair the breaks in the relationships. Conflict is a natural part of any human system. If the supervisor handles the situation appropriately, it increases trust and safety within the milieu.